When German Female Prisoners Arrived in America, They Expected the Worst

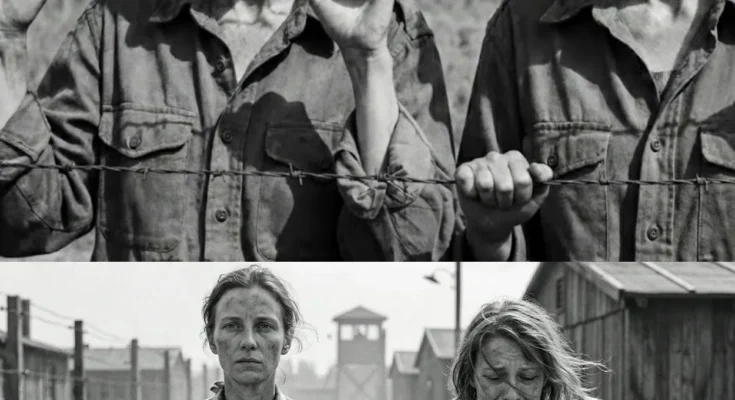

The women expected punishment.

When the truck finally stopped, none of them spoke.

Dust settled slowly in the warm American air, drifting over barbed wire fences and wide open fields.

This was nothing like the camps they had known in Europe.

No shattered buildings, no smoking ruins, just land, endless land.

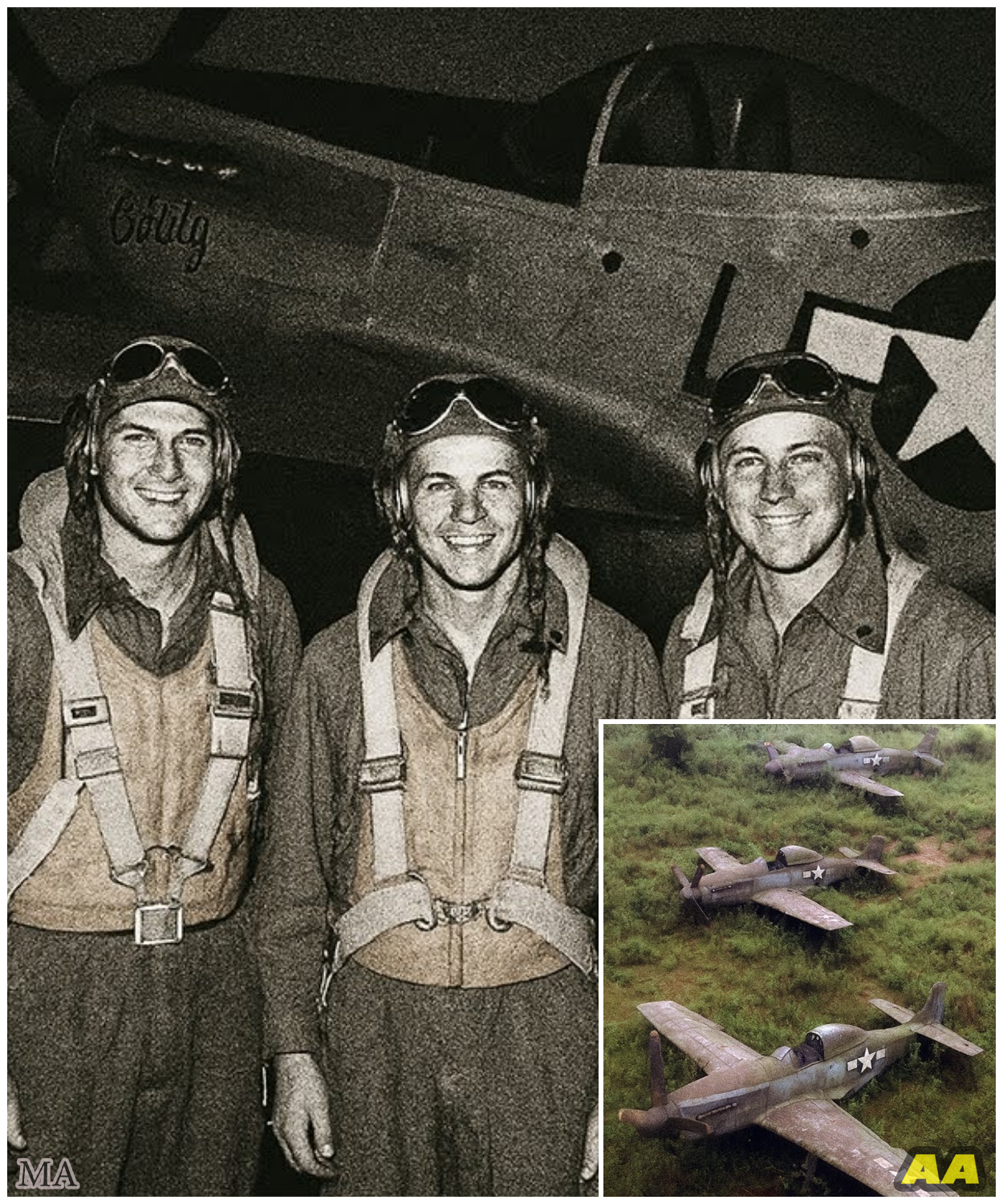

They were German prisoners of war.

Women who had worked in factories, offices, and supply units during the final months of the war, now captured, transported across the ocean, and delivered deep into the American interior.

A guard read their orders calmly.

You’ll be assigned to agricultural labor.

The words hit them like a sentence.

Farm work meant long hours, heavy lifting, no mercy for weakness.

Back home, they had seen what happened to prisoners who slowed down.

No excuses, no rest.

One woman whispered, barely audible, “We won’t survive this.” The gate opened.

On the other side stood men they had never imagined seeing.

American cowboys, wide-brimmed hats, rolled up sleeves, boots worn smooth by dirt and sun.

Some leaned against fences, others chewed straw.

They didn’t shout.

They didn’t stare with hatred.

They simply watched.

An American officer gestured toward the group of women.

These are your workers.

For a long moment, no one moved.

Then one of the cowboys stepped forward.

He was older, weathered, his face lined by years of wind and sun.

He looked at the women, their thin frames, hollow cheeks, tired eyes.

He didn’t smile.

He shook his head.

Finally, he spoke.

You’re too weak to work.

The women froze.

They expected yelling next, insults, punishment for disappointing him.

Instead, the cowboy turned back to the officer.

They won’t last a day like this.

The officer frowned.

They’re prisoners.

The cowboy didn’t argue.

He simply said, “Then feed them first.” That single sentence stunned the women more than anything they had experienced since their capture.

Food was brought out.

Real food, bread, meat, milk, not scraps, not leftovers.

The women hesitated, afraid it was a test.

But no one rushed them.

No one shouted.

One by one, they ate.

And for the first time since the war had ended, something unfamiliar crept in.

Not hope, but confusion.

Why were these men acting this way? What did American cowboys want from enemy prisoners? They didn’t know it yet, but this farm would change everything they believed about captivity, power, and dignity.

The next morning came quietly.

No whistles, no shouting.

The women woke before sunrise out of habit, tense, and ready for punishment that never came.

Outside, the farm was already alive, not with guards barking orders, but with the sound of animals, boots on dirt, and low conversation.

One by one, the cowboys arrived.

They didn’t carry weapons.

They didn’t hurry the prisoners.

Instead, an older man spoke in slow, clear English, using gestures when words failed.

Work slow.

Learn first.

The women exchanged glances.

That was not how labor camps worked.

Back home, mistakes were punished.

Weakness was mocked.

Here, the first task wasn’t lifting.

It was watching.

They were shown how to feed animals, how to carry tools properly, how to rest without asking permission.

When one woman’s hands started shaking, she stepped back instinctively, bracing for anger.

None came.

A cowboy noticed and simply said, “Sit.

Drink water.” She sat.

Nothing happened.

Later that day, one of the women dropped a heavy bucket.

It spilled into the dirt.

She froze, heart pounding, already preparing apologies in her mind.

The cowboy sighed, not in anger, but frustration with the task itself.

“Too much weight,” he muttered, then replaced it with a lighter one.

The women began to realize something unsettling.

“These men were not trying to break them.

They were trying to keep them alive.” At midday, the work stopped, not slowed, stopped.

Food was served again.

enough food.

One woman whispered, “Why are they doing this?” No one had an answer.

That afternoon, the officer returned to inspect progress.

He expected complaints.

Instead, the cowboys told him plainly, “They’ll work tomorrow, too, if you let them rest today.

” The officer hesitated, then nodded.

That night, lying on their bunks, the women stared at the ceiling, unable to sleep.

For the first time since capture, their bodies achd not from punishment, but from honest work done without fear.

And for the first time, a dangerous thought entered their minds.

What if captivity didn’t have to mean humiliation? They didn’t know it yet, but tomorrow would test that idea in ways none of them expected.

On the third day, something changed.

The women noticed it immediately.

The cowboys were gone.

No hats on the fence, no boots in the dust.

Only the officer remained, standing near the barn, clipboard in hand.

He watched as the women gathered, unsure what to do.

This was usually when rules tightened, when freedom vanished.

Then the officer spoke.

You know the work now.

He pointed toward the fields.

You’ll do it yourselves today.

No escort, no shouting, just instructions and distance.

The women hesitated.

Back home, this would have been a trap, a test designed to expose weakness or disobedience.

One wrong move could mean punishment for all.

Slowly, they began.

They fed the animals.

They cleaned tools.

They worked in silence, watching one another.

Hours passed.

Nothing happened.

No one was rushed.

No one was punished for resting.

When one woman struggled to lift a crate, another stepped in without fear of being accused of laziness.

At midday, the officer returned.

He looked over the work, then the women.

“Good,” he said simply.

He placed the clipboard down.

“Take a break.” The words didn’t register at first.

“A break without asking.” Some of the women sat in the shade.

Others stared at the open fields beyond the fence.

Land so wide it felt unreal.

One woman whispered, “They trust us.” The realization was unsettling.

Trust had always been dangerous.

It was given, then taken away, used as leverage.

Here it felt different.

That evening, the cowboys returned.

They checked the animals, the tools, the work.

No complaints.

One of them nodded.

Tomorrow, he said, “We’ll work together.

” That night, something new spread through the barracks.

Not relief, not happiness, but something fragile and unfamiliar.

Confidence.

They were still prisoners, but for the first time they felt treated like people, and tomorrow would prove whether that trust was real or temporary.

The change didn’t happen all at once.

It happened quietly, the way real change often does.

Weeks passed.

The women worked alongside the cowboys now, not separated, not watched from a distance.

They learned names, simple jokes, the rhythm of the land.

No one shouted when mistakes happened.

No one punished slowness.

When one woman collapsed from exhaustion one afternoon, work stopped completely.

Not just for her, for everyone.

The cowboys carried her to the shade.

Water was brought.

A doctor was called.

The officer arrived later, already informed.

“She won’t work today,” the cowboy said flatly.

The officer looked at the woman, then nodded.

That moment spread faster than any rumor.

Back in the barracks that night, the women whispered in disbelief.

They stopped everything for one of us.

They had been told all their lives that defeat meant humiliation, that prisoners existed only to be used.

Here they were learning something dangerous, that power didn’t always need cruelty.

As the months went on, letters were allowed.

Proper clothes replaced worn uniforms.

Some women were reassigned to lighter duties, kitchens, offices, caring for animals.

No one mocked weakness.

One evening, as the sun set over the fields, an older cowboy sat on a fence and spoke quietly to one of the women.

You know, he said, “Works work, but people are people.” She didn’t answer.

She didn’t need to.

When the war finally ended and repatriation orders came, the women packed in silence.

No celebration, no cheering.

Leaving felt complicated.

On the last day, the cowboys stood by the gate.

No speeches, no ceremony, just nods.

One woman hesitated, then spoke softly.

You didn’t have to treat us this way.

The cowboy shrugged.

Didn’t see another way.

Years later, many of those women would struggle to explain their time in captivity because it didn’t match the stories people wanted to hear.

They had been prisoners.

But on an American farm, among strangers in hats and boots, they had been treated for the first time in years like human beings.